Tony Lord: Have you had your five portions of fruit?

I must tell you right away that I find it very difficult to consume the five portions of fruit which dietitians want us to eat daily.

Pears and peaches are hard when they arrive from distant orchards and one spends the following days gently caressing them to discover if they’ve ripened up.

Foreign apples are often hard and tasteless and one has to wait until September to enjoy the delicious taste of English Cox’s Pippins, Russets and baked Bramleys stuffed with sultanas.

So one is left with a choice of bananas, dried fruit such as apricots, dates or dried figs which tend to have disastrous consequences for me as night falls.

Thank goodness for juicy oranges which these days arrive by aeroplanes from all over the world. Sweet oranges were first mentioned in Chinese literature as early as 314 BC and were introduced into the Mediterranean area by early navigators in the 16th century.

Later some orange trees were brought to England and were cultivated by wealthy people in private conservatories known as orangeries.

Certainly Nell Gwynn (1650-87) was selling them (and other favours) around Drury Lane until she caught the eye of Charles II, which meant she didn’t have to hawk her fruit around anymore.

I usually buy my oranges in Lewisham Market and try to find a stall where the proprietor has cut a couple of his oranges in half and is displaying them to show how juicy they are.

The traders are not happy when I pick one up, suck it and then say it’s too stringy and move away. Usually, one can buy six for a pound.

I remember before the war down there you could buy half a dozen in a brown paper bag for sixpence, a penny each.

We would have laughed if someone had told us that 80 years later one orange would cost nearly four shillings in old money.

My mother always liked to have a bowl of fruit on the sideboard. She was constantly telling me not to touch them but I became adept at making a bowl of apples, pears, grapes and four oranges become a bowl of apples, pears and three oranges without her noticing.

I used to eat the orange down at the end of the garden in the old shed and bury the peel in the earth outside. I think she was too vain to wear glasses and the young master criminal was never found out.

Ten years or so later, in 1945, I got into a bit of a scrape over a basket of oranges in the City of Saigon, the capital of French Cochinchina.

Our hospital ship had steamed up river to pick up the families of French settlers who were being threatened by rebel communists who wanted independence for their country.

Everything seemed peaceful in ‘The Paris of the East’, as Saigon was known, so our gallant band of doctors and medics were given leave to stroll around the boulevards provided we were back on board by nightfall because it was considered dangerous to be abroad in the darkened city.

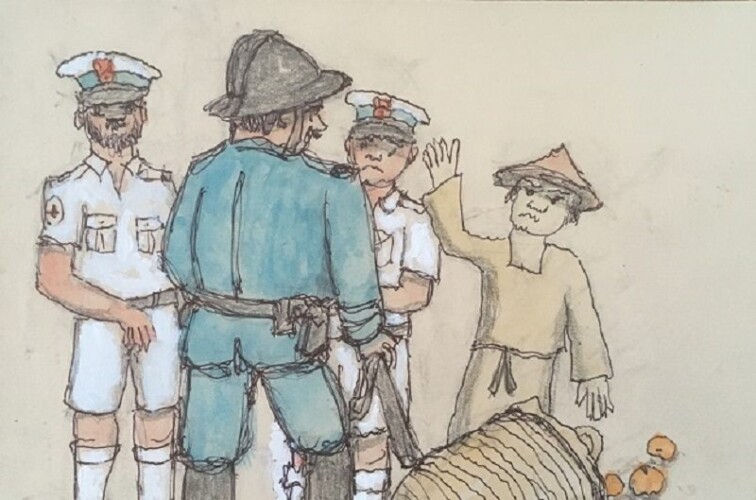

Sid and I were walking towards a cafe with tables outside when we came upon a French gendarme who, baton in hand, had kicked a young woman’s basket off the pavement sending scores of oranges rolling over the road.

The policeman had a brutal, bully’s face and a pistol in his belt.

We were stupid enough to protest at this needless, spiteful act and Sid started to help the woman retrieve the oranges.

Now this was a time when the French had no liking for us, saying we had run away at Dunkirk in 1940 leaving France to be occupied by the Germans.

The Frenchman shouted at Sid to stop helping the woman, and when Sid calmly carried on he drew his pistol and took us to the local gendarmerie where we were put in a cell.

As our ship was due to sail next morning it meant that it was quite possible that we would be left in a dangerous place 10,000 miles from home.

Fortunately one of our officers had seen what had happened and hurried back to the ship with the news.

This resulted in Captain Higgins, Chief Petty Officer Pearson and some of our mates arriving at the police headquarters as dusk fell, demanding our release.

Captain Higgins told the inspector in charge in no uncertain terms that no French refugees would be taken on board until we were released.

Realising that the whole affair was ridiculous, the cell door swung open, hands were shaken, apologies were made and we all hurried back to the ship.

Next morning 50 sad women came aboard with their belongings, we cast off the mooring ropes and steamed off down river, glad to leave that hot, humid city which would be so much in the news 20 years later during the Vietnam War.